Abstract

The objective of this research is to investigate Canadian criminal judges’ views on offences related to procuring, seeking, or controlling under-aged sex workers, and factors influencing sentence severity. A qualitative analysis was conducted on sentencing court reports in Canada obtained through the Canadian Legal Information Institute (CanLII) database. Twelve sentencing court reports that fit the criteria of inclusion were selected as samples. Data analysis and coding procedures were guided by theories put forth by Amirault and Beauregard (2014), and Kingsnorth, MacIntosh, and Wentworth (1999), in combination with a grounded theory approach. Results revealed that mitigating and aggravating factors, and existing provisions in the Criminal Code of Canada were the main factors influencing judges’ decisions on sentence severity. Furthermore, judges viewed these offences as inherently wrong, and attributed culpability entirely on the offender by referring to under-aged sex workers as vulnerable victims, and chastising offenders by referring to their behaviours as selfish and disgusting. Implications in relation to current societal views on sex-workers were discussed, and strategies for future research were suggested.

Introduction

The act of selling sex is not illegal in Canada, although communication and other activities related to obtaining sexual services from prostitutes have been prohibited by the Criminal Code of Canada (Criminal Code) (Shaver, 2011). The ground-breaking judgement in Canada (Attorney General) v. Bedford SCC 72 (2013) where the Supreme Court of Canada struck down several laws regulating activities related to prostitution (e.g. bans on street soliciting and brothels) illustrates our society’s changing views on sex workers. Prior to the Bedford case, feminist movements in the 1970’s challenged the constitutionality of Canada’s prostitution laws, arguing that sex workers should be viewed as victims and not criminals (Davies, 2015). Under this view, individuals who procure or exploit sex workers should be the ones criminalized (Rotenberg, 2016). Moreover, public perceptions towards sex offenders who target victims under 18 years old are overtly negative, and the public highly stigmatized them (Corabian & Hogan, 2015) due to the fact that children are often viewed as a vulnerable population (Bill C-2, 2005, “Summary”, (b)(c)). A heinous act victimizing under-aged sex workers would therefore create a ‘double-jeopardy’ in terms of severity of the crime.

Recent research has shown that the community’s attitude towards sex offenders are generally negative, propelled by beliefs that sex offenders are compulsive, incapable of changing their irrational behaviours, and socially withdrawn (Wevodau, Cramer, Gemberling, & Clark III, 2016). Additionally, Bumby and Maddox (1999) found that the public often demanded swift and extreme punishments for sex offenders, increased mandatory minimum sentences, and sex offender registries (the Sex Offender Information Registration Act (SOIRA) in Canada). As representatives of the public, judges are expected to accommodate the public’s concerns and attitudes towards sex offenders, and to uphold social justice through sentencing. Some studies have found that the public’s opinion on the ideal length of sentences is similar to what has been given by judges (Devilly & Le Grand, 2015). Additionally, other research has shown that judges have predisposed biases when it comes to sex offenders which align their opinions with public perceptions and would result in more punitive sentences when compared to non-sexual offenders (Rydberg, Cassidy, & Socia, 2017).

In Canada, §718.2 of the Criminal Code outlines sentencing principles, which considers mitigating and aggravating factors that judges would have to take into account when imposing sentences. Some studies have found that the main aggravating factor in influencing the length of prison sentence is prior criminality (Roberts, 2008). However, other studies have shown that judges consider offence-based characteristics (e.g. violent offences like rape or murder) as being more important than the characteristics of the victim or offender (Patrick & Marsh, 2011). In other words, judges find the act of the sex offence so heinous that it is considered an aggravating factor of its own. Further, Kingsnorth, MacIntosh, and Wentworth (1999) found that victims’ ‘negative’ characteristics (e.g. acts of prostitution) contributed to lower sentence severity for sex offenders. This finding suggests that, although the public may assign victimized roles to sex workers, the fact that sex workers ‘choose’ such a line of work could still present a mitigating factor when it comes to sentencing sex purchasers.

However, under-aged sex workers may be viewed differently. Literature has shown that child-sex offenders were sentenced more severely compared to other violent offences (Champion, 1988). In researching mitigating and aggravating factors on sentence severity among Canadian sex offenders, Amirault and Beauregard (2014) found that the victim’s age and physical violence towards the victim were strong aggravating factors for increased sentences. This finding is in accordance with Devilly and Le Grand’s (2015) research showing that the public believed imprisonment was more appropriate for sexual assault against children when compared to other types of offences. Although much research has been conducted in examining factors that contribute to the sentencing of sex offenders through quantitative analysis, there seems to be a gap in qualitative literature, which this study aims to fill. Thus, the research questions for this study are: 1) how do Canadian criminal court judges view offences related to procuring, seeking, or controlling under-aged sex workers?; and 2) how do they justify sentencing the offenders who were found guilty of the crime(s)?. Correspondingly, this exploratory study is guided by two theories outlined above: that 1) a victim’s age influences sentence severity (Amirault & Beauregard, 2014), and that 2) a victim’s negative characteristics act as a mitigating factor in sentencing (Kingsnorth et al., 1999; Horowitz, Kerr, Park, & Gockel, 2006).

Methods

Materials

Data was extracted from published Canadian court sentencing reports at the provincial level. These court reports represent the unobtrusive and non-live unit of analysis. Specifically, court reports were retrieved from the legal database provided by the Canadian Legal Information Institute (CanLII). Twelve reports represented the final sample for this study.

Sampling procedure

Based on the research question of this study, the following criteria of inclusion were applied: 1) criminal court reports of offences involving the procuring, seeking, or controlling of sex workers, 2) cases with victims under the age of 18, 3) court reports from provincial courts, 4) cases of convicted and sentenced individuals, 5) sentence length of at least 12 months, and 6) court reports of reasons for sentences. For criteria five, the Criminal Code specifies that less serious offences (summary offences) will result in a sentence of 2 years less-a-day, whereas more serious offences (indictable offences) will result in sentences of at least 2 years. Thus, in order to include a wider spectrum of crime severity, the decision was made to include cases that were on the higher end of summary sentences spectrum (i.e. 1 year to 2 years less-a-day). Further, to ensure that this sample is representative of Canada, a stratified purposive sampling (i.e. samples within samples) was employed – cases were chosen from different provinces including six from Ontario, two from Nova Scotia, and one each from Manitoba, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Quebec. There were no cases from other provinces found in the CanLII database which satisfied the criteria of inclusion above. These cases were chosen to represent the sample as this will better reflect modern society’s views on the sexual exploitation of under-aged sex workers. The date range for this study’s data dated between 1993 and 2017.

Data analysis and coding

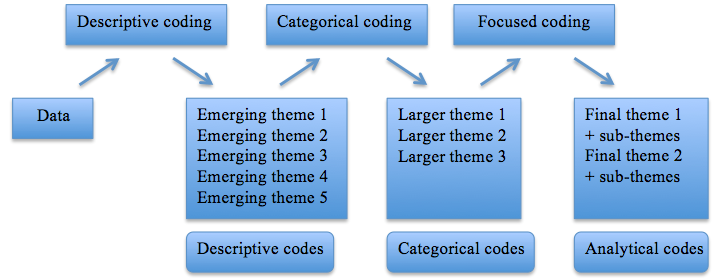

This study adopts both deductive and inductive methods in its analysis. In terms of deductive method, two theories from the literature guided the research question: that 1) a victim’s age influences sentence severity (Amirault & Beauregard, 2014), and that 2) a victim’s negative characteristics act as a mitigating factor in sentencing (Kingsnorth et al., 1999; Horowitz, Kerr, Park, & Gockel, 2006). This is coupled with an inductive approach using grounded theory analysis. Grounded theory is a method of analysis in which the development of theory follows analysis of the data itself (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Once the sample has been gathered, a first read-through of all the court reports were conducted. Each court report was tagged numerically (e.g. Case 1, Case 2). In this first read-through, broad emerging themes were highlighted for descriptive coding. Next, an Excel spreadsheet was created to record emerging themes and subthemes. In the second read-through, categorical coding was conducted, where descriptive codes found earlier were grouped together into larger themes. For the third read-through, focussed coding was conducted, where descriptive and categorical codes were compared against each other, which were then developed into analytical categories. These analytical categories were refined to include a broader interpretation of the data, where entire sentences or paragraphs were included in part of the analysis. Through a grounded theory approach, five main emerging themes were identified, along with corresponding subthemes (Figure 1). A fourth and final read-through was conducted on the sample to ensure that no new themes emerged, and reflexivity was performed throughout the analysis process to ensure that the data was appropriately categorized.

Results

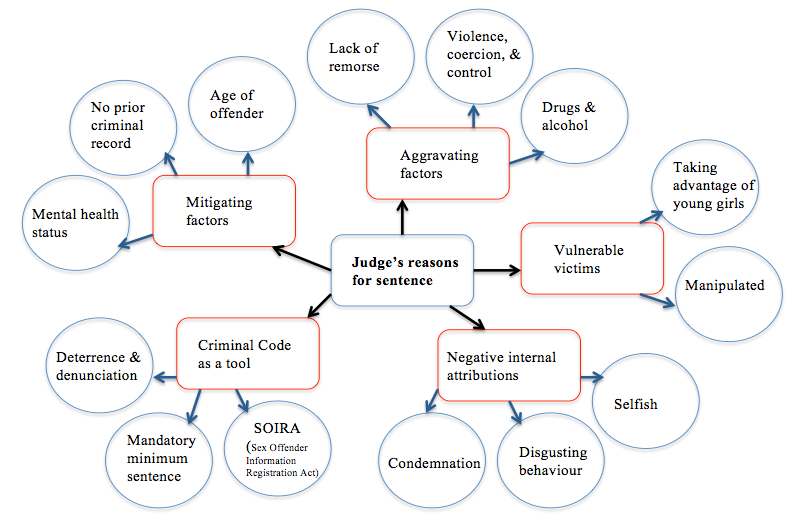

The present study identified five main themes related to judges’ reasons and views towards sentencing individuals who were convicted of offences related to procuring, seeking, or controlling under-aged sex workers: 1) mitigating factors, 2) aggravating factors, 3) vulnerable victims, 4) negative internal attributes towards the offender, and 5) the Criminal Code as a tool to guide sentencing. Each main theme further consisted of subthemes, as outlined in Figure 2.

Mitigating factors

In every court sentencing report, judges weighed mitigating factors surrounding the accused in determining the sentence severity; these factors were usually presented by the defence in hopes of a lighter sentence. Within mitigating factors, three subthemes emerged: 1) mental health, 2) lack of a prior criminal record, and 3) the offender’s age.

Mental health was a common mitigating factor that judges looked for in sentencing decisions as it decides the accused’s moral culpability. For example, in Case 12, the judge reiterated the defence’s arguments:

[…] defence counsel also urged the court to find that Mr. Finestone’s diagnoses of Autism Spectrum Disorder further serves to mitigate his circumstances as it played a contributing role in the offence before the court.

(Case 12, para. 51)

In the above case, the judge considered the accused’s mental illness but ruled that it appeared to be mild (according to expert testimony), and “…that it was not the only factor causing Mr. Finestone to commit this offence…” (Case 12, para. 58). Moreover, judges also look to any prior criminal record and the offender’s age:

I note Mr. Ackman’s age, that he has no past criminal record and that he has support in the community as significant mitigating factors.

(Case 2, para. 29)

[…] but he’s a young man and he enjoys the support of his family. There’s ample room for rehabilitation and that remains an important goal of sentence.

(Case 7, para. 11)

It is important to note that, although the lack of a prior criminal record and an offender’s being a young adult may serve as mitigating factors, judges seemed to put more weight on the seriousness of the offence itself, in which constitutes an aggravating factor.

Aggravating factors

Along with mitigating factors, judges also considered aggravating factors which surrounds the crime. This is usually put forth by the Crown in hopes of achieving the maximum penalty. In terms of aggravating factors, three subthemes were identified: 1) violence, control, and coercion, 2) drugs and alcohol, and 3) lack of remorse:

Mr. Moazami used violence and the threat of violence, intimidation and coercion in relation to M.N. during their association between 2009 and 2011. When M.N. first began working as a prostitute for Mr. Moazami, he used a threat of slapping her as a means of coercing her into accepting a client that she had initially refused to service.

(Case 1, para. 47)

The above example echoes Amirault and Beauregard’s (2014) finding that offenders who used violence to control the victim during the crime were given longer and harsher sentences, compared to offenders who did not use violence. Furthermore, offenders were judged more harshly if they introduced or provided illicit substances to under-aged sex workers during the commission of the crime. Illicit substances and alcohol abuse have been proven throughout the decades to have contributed to impaired attention, memory, and executive attention in adults (Luciana, M., Collins, P., Muetzel, R., & Lim, K., 2013), and the effects are much more detrimental to adolescents (O’ Shea, Singh, Mcgregor, & Mallet, 2004; Schubart et al., 2011). As exemplified by the judge in Case 1:

[…] he plied her with drugs and alcohol to ensure that she was physically and emotionally dependent upon him.

(Case 1, para. 70)

Previous research has shown that an offender’s signs of remorse (or lack thereof) can greatly influence the judge’s sentencing decisions. Offenders who did not provide statements of oral or written communications in recognition of wrongdoing were often seen as unremorseful, and were given harsher sentences (Zhong et al., 2014). In this current study, an offender’s choice to remain silent when given the opportunity to make a statement during sentence hearing, or claim that he did not know the sex workers were under-aged, were considered as aggravating factors:

[…] he has not shown any remorse or insight to his criminal behaviour. And, he has not accepted any meaningful responsibility for hurting or exploiting or exposing to danger any of the girls or young women.

(Case 2, para. 29)

This finding is contradictory to Amirault and Beauregard’s (2014) research results, where the authors found that an offender’s degree of remorse had no effect on sentence severity. One possible explanation is that victims in the present study’s sample were marginalized women. Failure on the offender’s part to recognize how his actions had caused physical and psychological damage to these victims speaks to his moral character, thus leading to an increase in sentence severity.

Vulnerable victims

Another emergent theme that surfaced from judges’ reasonings during sentencing was the view that under-aged sex workers were vulnerable victims. Particularly, judges view the offender as 1) taking advantage of young girls, and 2) manipulating them into the sex-work environment.

All of the offenders in this sample were adult males, and some were significantly older than their victims (highest range was 30 years). Judges took this into regard during sentencing, often viewing the offenders as “exploit[ing] underage women” (Case 4, para. 14). As one judge in Case 12 noted:

I draw from this that the coercion involved related to manipulation of a vulnerable young person as opposed to explicit or even implied threats or violence.

(Case 12, para. 37)

The above excerpt showed that the under-aged sex worker was viewed as a victim, despite her role as a sex worker. This is contrary to Kingsnorth et al.’s (1999) finding where a victim’s negative characteristics led to lower sentence severity. One possibility is that the victims in this study were minors and were thus viewed as vulnerable; any person who takes advantage of their vulnerability and innocence should be highly condemned, regardless of the victim’s background.

Negative internal attribution

The fourth theme that emerged from this study was the way judges attributed the offenders’ behaviours internally through 1) being selfish, 2) being disgusting, and that 3) they warranted condemnation.

Judges attributed the offences as acts of greed and self-centredness, “[…] a horrible display of vanity and self-aggrandizement” (Case 2, para. 37). Although certain mitigating factors may serve to lessen the severity of their sentences (e.g., no prior criminal record), judges did not hold back from verbalizing their perceptions of the offenders:

At the end of the day, Mr. Ackman is a middle-aged man with no past criminal record, who for no obvious reason except money and vanity happily wallowed in the grimy underbelly of the sex-trade business with its oft built-in exploitation and sexual abuse.

(Case 2, para. 45)

Mr. Moazami’s treatment of H.W. was abusive, callous, and borders on psychopathic. She was his property to sell and to misuse.

(Case 1, para. 112)

Well informed members of our community would be shocked and disgusted by Mr. Moazami’s conduct.

(Case 1, para. 71)

This finding is reminiscent of Rydberg et al.’s (2017) study where they found judges tend to hold negative stereotypes for sex offenders mirroring the public’s attitude. Offenders who took advantage of under-aged sex workers, whether to procure them, seek their services, or control them were labelled “parasites of our society” (Case 12, para. 76) in judges’ eyes. This negative inclination against offenders will no doubt have an immense effect on the severity of their sentence.

Criminal Code as a tool

The final theme that emerged from this study was the judges’ referring to existing legislations and regulations (the Criminal Code) that were used as tools to establish sentencing decisions. Particularly, judges pointed to 1) mandatory minimum sentences, 2) deterrence and denunciation, and 3) SOIRA.

In all of the reports sampled, judges made references to the mandatory minimum sentence outlined in §212 (2.1) of the Criminal Code, which specifies that the offence of “living off the avails of child prostitution” mandates a minimum 5 years’ imprisonment sentence. Although judges referred to precedent cases to help them determine the sentence for the case at hand, existing provisions like mandatory minimum sentences played a larger role in the judge’s decision in order to deter and denounce such acts:

It is clearly a sentence that reflects Parliament’s intention that certain designated offences be subject to a minimum sentence due to their serious nature. Further, I find that the sentencing provisions of the Criminal Code reflect the community’s belief that offenders should be required to serve at least the minimum sentence for each offence they commit against young persons.

Case 1, para 141)

This reflects, without a doubt, the position of Courts across the country stating that deterrence and denunciation were paramount when determining the appropriate sentence in such cases.

(Case 4, para. 8)

More than half of the reports sampled resulted in the judge ordering a SOIRA order against the offender, ranging from 10 years to a lifetime. Research has found that the public were generally supportive of swift and harsh punishments for sex offenders (Bumby & Maddox, 1999; Levenson, Brannon, Fortney, & Baker, 2007), which include mandatory minimum sentences and SOIRA. Further, according to Devilly and Legrand (2015), the lengths of sentences imposed by judges on sex offenders were found to be similar to what the public would like to have imposed as well. This relationship is evident in the current study, where judges agreed with the attitudes and beliefs of the public as found in previous literature (Levenson et al., 2007) with regards to offenders who exploit under-aged sex workers.

Discussion

This study’s aim was to uncover and investigate Canadian criminal court judges’ views on offences related to procuring, seeking, or controlling under-aged sex workers, and what factors influenced judges’ decisions on sentence severity. Through a combination of deductive and inductive analysis, five main themes were uncovered. In terms of judges’ views on offenders, it was found that judges made negative internal attributions – the offender was selfish, his behaviour was disgusting, and warranted high condemnation. This negative view on the offender’s personality is congruent with Rydberg et al.’s (2017) findings that sex offenders were usually more negatively stereotyped than non-sex offenders. Furthermore, the culpability for these crimes against under-aged sex workers was placed entirely on the offenders. There were no indications that the victims’ negative characteristics mitigated the seriousness of the offence, contrary to Kingsnorth et al.’s (1999) findings. In fact, judges viewed under-aged victims as vulnerable victims who were manipulated or taken advantage of by offenders. This could possibly be due to society’s changing views on sex-workers (Weitzer, 2015), under which they are viewed as victims, placing the blame on sex purchasers.

In terms of factors that influenced judges’ decisions on sentence severity, results showed that judges weighed both mitigating and aggravating factors. In line with previous studies, the victim’s age and presence of violence were significant factors that led to an increase in sentence severity (Amirault & Beauregard, 2014; Patrick & Marsh, 2011). Contrarily, judges in the current study also weighed mitigating factors like the offender’s mental health and lack of previous criminal convictions when handing out sentences (Crawford, 2000; Frase, 2010). In addition, judges were also found to rely heavily on available sentencing provisions outlined in the Criminal Code by referring to mandatory minimum sentences, and SOIRA while emphasizing the need to impose punitive sentences to achieve deterrence and denunciation of such crimes.

Findings from this study provides a qualitative insight into how Canadian judges view offenders who exploit under-aged sex workers, and to peek into the inner workings of judges’ rationality in determining the severity of the sentences. It is interesting that, although judges are seen as trying to remain impartial during sentencing, heuristics and biases against offenders do play a hand in justifications for sentences. This is exemplified by judges referring to offenders’ negative internal attributions, and how under-aged sex workers were victims in the hands of these “parasites” (Case 12, para. 76). Thus, the offence of exploiting under-aged sex workers is seen as mala in se (wrong or evil in itself). This study is not without its limitations: the coding and analysis process involved four read-throughs of the sample – however it was only conducted by the primary researcher. Limited resources and time prevented the possibility of a second coder, which could have increased its validity through inter-rater reliability checking. Furthermore, although 12 sentencing court reports were carefully selected to represent the sample, data saturation could not be achieved as the database (CanLII) did not contain sentencing reports from other Canadian provinces besides the six that were surveyed for this study. Future studies could include court reports where sentences were served in the community or were less than 12 months in length.

Future research could examine as to how much effect personal biases and heuristics towards victims have in the role of sentencing. An example could include a survey administered to judges using the Community Attitudes Toward Sex Offenders (CATSO) scale, in which an 18-item self-report questionnaire measures the respondents’ attitudes towards sex offenders (Harper, & Hogue, 2015; Wevodau et al., 2016). Items like risk perceptions, stereotype endorsement, and punitiveness within CATSO can help shed some light into the general attitude of the judges and compare the results to their responses concerning non-sex offenders. Future research could also look into whether the existing legislative tools are enough to justify appropriate penalties for offences against vulnerable victims. These questions can add to the sparse qualitative literature on sex offences.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Jennifer Kusz and Dr Eric Beauregard for “their guidance and help”.

References

- Amirault, J., & Beauregard, E. (2014). The Impact of Aggravating and Mitigating Factors on the Sentence Severity of Sex Offenders: An Exploration and Comparison of Differences Between Offending Groups. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 25(1), 78–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403412462234

- Bumby, K., & Maddox, M. (1999). Judges’ Knowledge About Sexual Offenders, Difficulties Presiding Over Sexual OffenseCases, and Opinions on Sentencing, Treatment, and Legislation. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 11(4), 305-315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403412462234

- Bill C-2: An Act to Amend the Criminal Code (Protection of Children and Other Vulnerable Persons) and the Canada Evidence Act. (2005). 1st Reading Oct. 8, 2004, 38th Parliament, 1st session. Retrieved from the Parliament of Canada website: https://www.parl.ca/LEGISINFO/BillDetails.aspx?billId=1395588&Language=E

- Canada (Attorney General) v. Bedford, [2013] SCC 72.

- Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics (2016). Prostitution offences in Canada: Statistical trends. (Catalogue no. 85-002-X). Ottawa: Roternberg, C. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2016001/article/14670-eng.pdf

- Champion, D. (1988). Child Sexual Abusers and Sentencing Severity. Federal Probation, 52, 53-57. Retrieved from http://www.llmc.com.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/docDisplay5.aspx?set=80504&volume=1988&part=001

- Corabian, G., & Hogan, N. (2015). Attitudes Towards Sex Offenders in Canada: Further Validation of the CATSO-R Factor Structure. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 22(5), 723-730. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2014.985623

- Crawford, C. (2000). Gender, race and habitual offender sentencing in Florida. Criminology, 38(1), 263-280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2000.tb00890.x

- Criminal Code of Canada, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46.

- Davies, J. (2015). The criminalization of sexual commerce in Canada: Context and concepts for critical analysis. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 24(2), 78–91. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.242-A9

- Devilly, G., & Le Grand, J. (2015). Sentencing of Sex-Offenders: A Survey Study Investigating Judges’ Sentences and Community Perspectives. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 22(2), 184-197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2014.931324

- Frase, R. S. (2010). Prior-conviction sentencing enhancements: Rationales and limits based on retributive and utilitarian proportionality principles and social equality goals. In J. V. Roberts & A. von Hirsch (Eds.), Previous convictions at sentencing: Theoretical and applied perspectives (pp. 117-136). Portland, OR: Hart Publishing

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company.

- Harper, C., & Hogue, T. (2015). Measuring public perceptions of sex offenders: Reimagining the Community Attitudes Toward Sex Offenders (CATSO) scale. Psychology, Crime & Law, 21(5), 452-470. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2014.989170

- Horowitz, I. A., Kerr, N. L., Park, E. S., & Gockel, C. (2006). Chaos in The Courtroom Reconsidered: Emotional Bias and Juror Nullification. Law and Human Behavior, 30(2), 163-181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-006-9028-x

- Kingsnorth, R., MacIntosh, R., & Wentworth, J. (1999). Sexual Assault: The Role of Prior Relationship and Victim Characteristics in Case Processing. Justice Quarterly, 16(2), 275-302. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418829900094141

- Levenson, J. S., Brannon, Y., Fortney, T., & Baker, J. (2007). Public perceptions about sex offenders and community protection policies. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 7, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2007.00119.x

- Luciana, M., Collins, P., Muetzel, R., & Lim, K. (2013). Effects of alcohol use initiation on brain structure in typically developing adolescents. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 39(6), 345-355. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2013.837057

- O’Shea, M., Singh, M. E., Mcgregor, I. S., & Mallet, P. E. (2004). Chronic cannabinoid exposure produces lasting memory impairment and increased anxiety in adolescent but not adult rats. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 18(4), 502–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/026988110401800407

- Patrick, S., & Marsh, R. (2011). Sentencing Outcomes of Convicted Child Sex Offenders. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 20, 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2011.541356

- Roberts, J. (2008). Paying for the Past: The Recidivist Sentencing Premium. In Punishing Persistent Offenders. (pp. 1-25). New York, NY: Oxford University Press Inc.

- Rydberg, J., Cassidy, M., & Socia, K. (2017). Punishing the Wicked: Examining the Correlates of Sentence Severity for Convicted Sex Offenders. J Quant Criminol, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-017-9360-y.

- Schubart, C. D., van Gastel, W. A., Breetvelt, E. J., Beetz, S. L., Ophoff, R. A., Sommer, I. E. C., Kahn, R. S., & Boks, M. P. M. (2011). Cannabis use at a young age is associated with psychotic experiences. Psychological Medicine, 41(6), 1301–1310. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171000187X

- Sex Offender Information Registration Act, S.C. 2004, c. 10.

- Shaver, F. (2011). Prostitution. Historica Canada. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/prostitution/

- Weitzer, R. (n.d.). Human Trafficking and Contemporary Slavery. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 223-242. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112506

- Wevodau, A., Cramer, R., Gemberling, T., & Clark III, J. (2016). A Psychometric Assessment of the Community Attitudes Toward Sex Offenders (CATSO) Scale: Implications for Public Policy, Trial, and Research. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 22(2), 211-220. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000066

- Zhong, R., Baranoski, M., Feigenson, N., Davidson, L., Buchanan, A., & Zonana, H. V. (2014). So you’re sorry? The role of remorse in criminal law. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 42(1), 39–48.